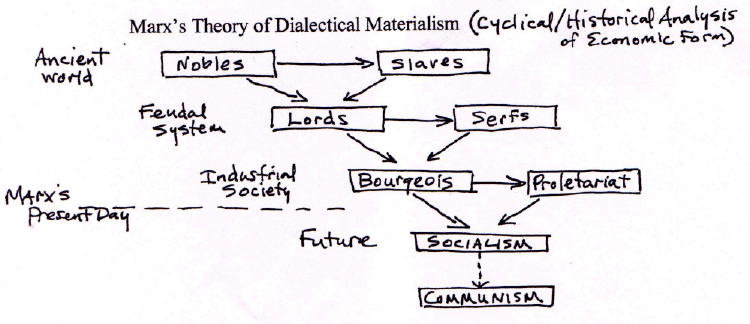

He wrote that Hegelianism stood the movement of reality on its head, and that it was necessary to set it upon its feet. While Marx accepted this broad conception of history, Hegel was an idealist, and Marx sought to rewrite dialectics in materialist terms. For example, Hegel strongly opposed the ancient institution of legal slavery that was practiced in the United States during his lifetime, and he envisioned a time when Christian nations would radically eliminate it from their civilization.

Sometimes, Hegel explained, this progressive unfolding of the Absolute involves gradual, evolutionary accretion but at other times requires discontinuous, revolutionary leaps - episodal upheavals against the existing status quo. Hegel believed that the direction of human history is characterized in the movement from the fragmentary toward the complete and the real (which was also a movement towards greater and greater rationality). Marx's view of history, which came to be called the materialist conception of history (and which was developed further as the philosophy of dialectical materialism) is certainly influenced by Hegel's claim that reality (and history) should be viewed dialectically. Consequently, most followers of Marx are not fatalists, but activists who believe that revolutionaries must organize social change. However, Marx famously asserted in the eleventh of his Theses on Feuerbach that "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways the point however is to change it", and he clearly dedicated himself to trying to alter the world. Some followers of Marx concluded, therefore, that a communist revolution is inevitable. Marx believed that he could study history and society scientifically and discern tendencies of history and the resulting outcome of social conflicts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)